|

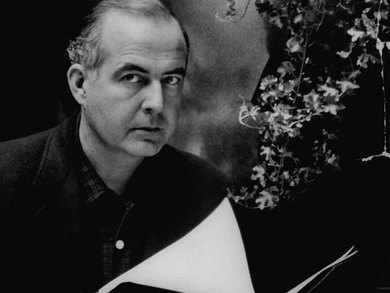

Like Pachelbel with his Canon, or Allegri with his Miserere, Samuel Barber has become one of those composers who is mostly remembered for just one piece, the grief-stricken arrangement for string orchestra of a movement from his Opus 11 quartet that has become known simply as “Barber’s Adagio”.

If you’ve seen already Barber’s name on our summer concert posters you may possibly be expecting us to sing the later reincarnation of the “Adagio”, set to the words of the Agnus Dei, but we’re singing reincarnations of an entirely different nature. |

The three part songs that make up the set called Reincarnations draw together all the themes of our summer concert: Ireland, America, love and home. Barber’s mother came from Irish descent and he turned to Irish poetry on a number of occasions – his solo vocal works include settings of Yeats, Joyce and medieval Irish texts. The texts Barber uses in Reincarnations are by the Irish poet James Stephens, drawn from a larger collection with the same name, which in turn are Stephens’s own translations from the Irish of poems by Antoine Ó Raifteirí (usually known in English as Raftery). Raftery was the last of the great Irish itinerant bards: blind from a young age, he wandered the country, taking shelter where it was given in return for his poetry and songs.

Stephens called his work Reincarnations because he felt his own Irish language skills weren’t good enough to justify calling his poems translations. It’s a particularly apt title though, as Barber’s songs stand at the end of a chain of reincarnations: Barber giving musical life to Stephens’s poems; Stephens bringing Raftery’s voice to a wider English-speaking audience; and Raftery himself creating vivid portraits of real people, who come back to life when we sing about them.

Mary Hynes, the subject of the first song, was a legendary beauty, known as “the shining flower of Ballylee”. Although a poor peasant girl, she dressed only in radiant white, and was said to have refused eleven offers of marriage in one day, and another drowned, drunk, in a bog after travelling to see her – although in the end, she succumbed to a rich seducer who abandoned her, and cast out by the community she died of pneumonia. Raftery’s original poem runs to many more verses than Barber and Stephen’s version: Mary’s beauty must have been truly dazzling for a blind man to write such passionate verse to her. Barber’s music pours out praise of her beauty and womanly qualities in a stream of passion that pauses only to declare “she is the love of my heart”, before ending with a lyrical picture of the girl and her home town.

Anthony O’Daly was quite a different character. He was a member of the Whiteboys, a group who resisted encroachments on peasants’ rights to their land with a mixture of rent strikes and violence. In 1820, Daly was wrongfully accused of shooting at a local landowner, and condemned to hang, and although the local population acclaimed him as a hero and attempted to help him escape the gallows, he went quietly to his death.

Anthony! Since your limbs were laid out the stars do not shine! The fish leap not out in the waves! On our meadows the dew does not fall in the morn, for O’Daly is dead!

Barber’s song feels like a huge public outpouring of grief. It begins with the basses repeating Anthony’s name on a drone, whilst the upper voices sing a keening melody, and the piece builds to hysteria as the sopranos and altos take over the chanted name. There are also suggestions that Raftery’s poem is not a lament but a traditional poet’s curse, calling down retribution in response to Raftery’s own outrage at Daly’s execution.

After the passion and intensity of the first two songs, The Coolin brings sweet tranquility, and some exquisite music from Barber: it’s in this song that we can see the composer of the “Adagio”. The word “coolin” simply means a sweetheart, deriving from a word for a curl of hair, and variations of the song go back far beyond Raftery. The words sing about a couple who are so comfortable with each other and so deeply in love that they need no more words; it’s enough for them to hold hands, and look into each other’s eyes whilst they share a drink, cuddled together under a coat, on the hillside, perhaps looking out at the view on our concert poster. The music lilts along gently, suggesting a folk song, and there are some truly ravishing shifts of harmony as this set of very different songs draws to a peaceful close.