This summer programme is designed to speak to the rich eclectic collection of art drawn together at The Bowes Museum by John and Joséphine Bowes. In a first half of sacred music from the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, we reflect on the European connections that brought great work by El Greco and Canaletto to England. In the second half of the concert, we imagine ourselves at home in a grand nineteenth-century Anglo-French salon, with English and French music that touches more broadly on the landscapes and love stories hinted at in the artwork of Joséphine herself.

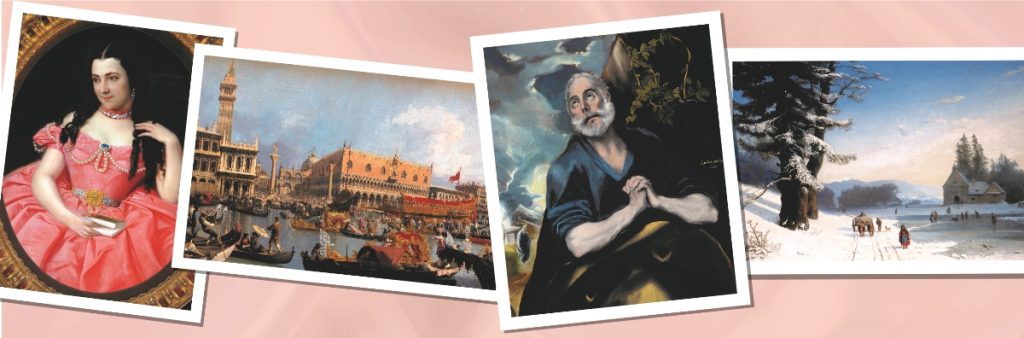

Our programme starts with a stunning piece of 12-part counterpoint by the Jacobean composer Thomas Tomkins, O Praise the Lord. The intricate way the voices are interwoven reminds me of the beautiful lace collar or Cloak band (c.1635) which the museum celebrates as one of its 25 treasures. Then we present two works, one by El Greco’s direct contemporary Orlando di Lasso, the other by the French baroque composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier, that tell the story of St Peter’s denial of Christ and the tears he wept as the meaning of his denial came home to him. Di Lasso, who was composing in the sixteenth century, worked in places such as his home in Flanders, Italy and finally Bavaria; rather like the complex international connections of the Bowes collection, the little piece we sing tonight (from a set of devotional madrigals in Italian meditating on Peter’s denial) makes the point that the great religious art of the renaissance and baroque travelled as much as the artists and composers who produced them. This particular madrigal, Come falda di neve, describes the tears of Peter like the melting of snow – and snow is a theme we will return to later. Charpentier’s Le reniement de Saint Pierre is a mini-cantata in which Jesus and Peter are sung by soloists, with interjections from the chorus, and it concludes with a remarkable piece of slow counterpoint, evoking the emotional response of the apostle. Like much of the French furniture in the collection, Charpentier’s setting is made up of styles that are both fresh and new, and that pay tribute to older form and line.

Cardinal Ottoboni was a great patron of the arts and sponsored Vivaldi, Corelli and other leading figures of Italian baroque music. Antonio Lotti benefited in Venice, like many others. His Crucifixus is a beautiful and widely popular moment from one of his mass settings, and it connects us both to the Italian music of the early 1700s and to the older crucifixion scenes that are at the heart of the sacred collection at The Bowes Museum. The greatest of the older Venetian composers, Monteverdi, wrote Lauda Jerusalem for Mantua. In spite of that, this of all the parts of his famous Vespers reminds me of great celebratory scenes from Venice such as those depicted a few decades later by Canaletto.

When we return after the interval, we perform music from nineteenth-century France in honour of Joséphine and her own love of nature, colour and art, but we keep the English connection with the famous madrigal The silver swan by Orlando Gibbons, and a twentieth-century partsong Walking in the snow by Herbert Howells, setting lines by his contemporary John Buxton. There are lovely snow scenes throughout the nineteenth-century part of the collection, and this is a love song in a winter landscape. It starts with a lonely wanderer, and the cold stillness of the snow-bound wood is evoked in haunting harmonies until the music opens suddenly into a fresh bright B major when the lover appears: ‘Oh! let the snowflakes nestle so lightly in your hair As if the wind had won you Jewels from the air.’

If we imagine Joséphine in one of her own paintings, perhaps – if not the lover in the snow – she might be resting under one of the majestic oaks in her 1867 and 1868 salon contributions Lisière d’un Forêt or Souvenir de Normandie: soleil couchant. The stillness of the night and the poet’s deep understanding of quiet is described in the first of Saint-Saëns’ opus 68 set, Calme des nuits. In this amazing spacious choral miniature, the brightness of the worldly day is left behind. And in Les fleurs et les arbres, eternal nature is married with art to light up our laughter and our tears – the still lives, landscapes, bronzes, statues and jewels of the collection coming together in a beautiful miniature. Charles Gounod, while known particularly for his operas, occasionally wrote sacred music, and Prière du soir seems to take the secular stillness captured in Joséphine’s French landscapes and marry it to a spiritual sentiment, echoing Calme des nuits in its evocation of dying light and peaceful contemplation, this time insisting that the evening is for God.

Two English works are added to our programme tonight at Brancepeth. A gorgeous twenty-first-century work, worthy of any of the jewels in the collection, Cecilia McDowall’s The skies in their magnificence sets Thomas Traherne with a slowly shifting palette of harmonic colour that exposes different resonance and overtones: ‘rare splendours, yellow, blue, red, white and green, mine eyes did everywhere behold’. And we conclude by bringing the musical conversation back to England, with a noble, festival anthem from the 1850s by Samuel Sebastian Wesley, Ascribe unto the Lord. In our concert at The Bowes Museum on 22 June, we perform Fauré’s secular hymn of praise to Venus; perhaps in this programme at Brancepeth we hear a solid English sacred counterpart: ‘as for the Gods of the heathen’ the choir sings in fugue, before striking down idols and a triumphant declaration ‘As for our God, he is heaven’. ‘The Lord hath been mindful of us’ provides a beautiful and melodious way of bringing this nineteenth-century Anglo-French salon to a close.

Julian Wright, Summer 2019